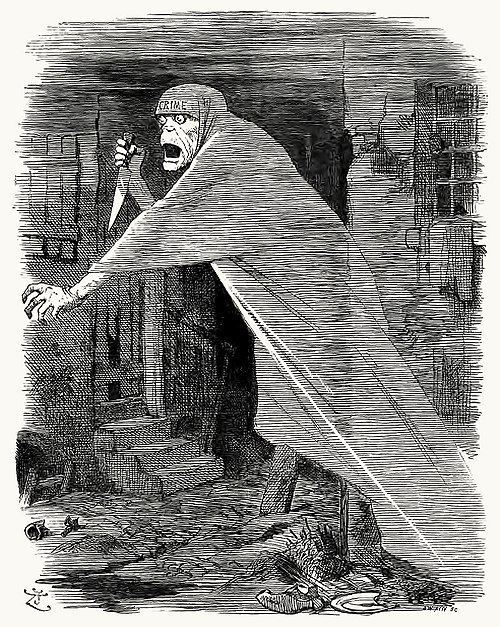

Few names evoke such immediate dread and fascination as

Jack the Ripper. For over 130 years, this unknown serial killer has haunted the annals of true crime, his gruesome deeds forever etched into the dark history of Victorian London. The Ripper’s reign of terror in the poverty-stricken streets of Whitechapel not only horrified a nation but also sparked a global obsession with solving one of history’s most baffling cold cases.

The East End in 1888: A Backdrop of Despair

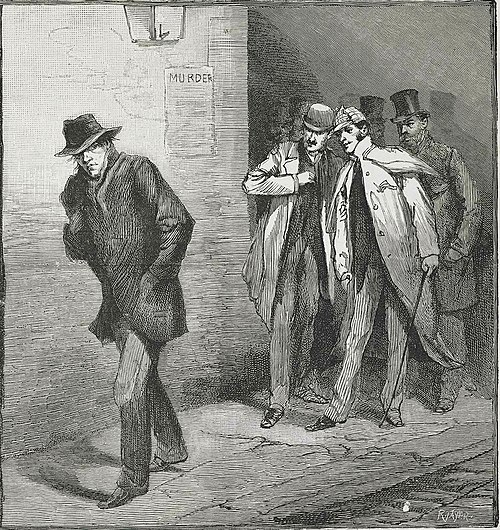

To understand the Ripper’s impact, one must first understand the setting. Whitechapel and Spitalfields in London’s East End during the late 19th century was a place of extreme poverty, overcrowding, and desperation. Slums teemed with the working poor, immigrants, and a vulnerable population, including numerous sex workers struggling to survive.

The police presence was minimal, and the gas-lit alleys were often shrouded in fog and shadows, providing the perfect cover for heinous crimes. Social tensions were high, fueled by economic hardship and class divides. This grim environment became the hunting ground for a killer who would capitalize on the area’s anonymity and the victims’ marginalization.

The Canonical Five: The Ripper’s Victims

While there were numerous unsolved murders in Whitechapel around this time, police and historians generally attribute five specific murders to Jack the Ripper, known as the “canonical five.” These victims were all female prostitutes, and their deaths shared a chilling pattern of brutal abdominal and genital mutilations, often suggesting some anatomical knowledge on the part of the killer.

- Mary Ann Nichols (“Polly”) – Murdered on August 31, 1888. Her throat was cut, and her abdomen was severely mutilated.

- Annie Chapman – Murdered on September 8, 1888. Similar throat wounds, and extensive abdominal and internal organ removal.

- Elizabeth Stride – Murdered on September 30, 1888. Her throat was cut, but no further mutilations, possibly due to interruption.

- Catherine Eddowes – Murdered on September 30, 1888 (the same night as Stride, known as the “double event”). Her throat was cut, and she suffered severe facial and abdominal mutilations, including the removal of a kidney and part of her uterus.

- Mary Jane Kelly – Murdered on November 9, 1888. This was arguably the most horrific of the murders, committed inside her room, indicating the killer had more time. Her body was extensively disemboweled and disfigured beyond recognition.

These murders occurred rapidly over just a few months, plunging London into a state of panic and fear.

The Letters: A Killer’s Taunts

Perhaps one of the most infamous aspects of the Jack the Ripper case is the series of letters purportedly sent by the killer to the police and media. While most are considered hoaxes, three stand out for their potential authenticity:

- “Dear Boss” letter: This letter, signed “Jack the Ripper,” is credited with giving the killer his notorious name. It taunted police about his activities.

- “Saucy Jacky” postcard: Arrived shortly after the “double event” murders, again mocking the authorities.

- “From Hell” letter: This chilling package contained half of a human kidney, believed to belong to Catherine Eddowes, along with a note that seemed to imply the other half was “fried and ate.”

These letters, whether genuine or not, fueled the hysteria and cemented the Ripper’s terrifying legend.

The Investigation: Frustration and Futility

The police investigation, primarily led by the Metropolitan Police (Scotland Yard) and the City of London Police (for Eddowes’ murder), was unprecedented for its time. Thousands of people were interviewed, house-to-house searches were conducted, and rudimentary forensic techniques were employed.

Despite intense efforts, public pressure, and numerous suspects, the killer was never caught or definitively identified. The lack of reliable forensic science, the absence of modern investigative techniques (like fingerprinting or DNA analysis), and the challenging environment of Whitechapel ultimately led to the case growing cold.

Suspects and Theories: An Enduring Obsession

The failure to identify Jack the Ripper has spawned countless theories and named dozens of suspects over the decades. These range from the plausible to the outlandish, including:

- Aaron Kosminski: A Polish Jewish barber, identified as the most likely suspect by DNA evidence in recent years (though this evidence remains highly debated and controversial among experts).

- Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale: A grandson of Queen Victoria, a popular, though largely unsubstantiated, theory.

- Montague John Druitt: A barrister who died shortly after the last murder, considered by some police officials to be a strong suspect.

- George Chapman (Seweryn Kłosowski): A Polish serial poisoner who later operated in London, though his modus operandi differed greatly.

- Dr. William Gull: The Queen’s physician, a sensationalized theory popular in fiction.

- And many, many more…

The lack of a definitive answer continues to fuel books, documentaries, tours, and academic debate, making Jack the Ripper one of history’s most popular true crime subjects.

The Ripper’s Legacy: A Dark Icon

Jack the Ripper remains an enigma, a shadowy figure who exploited the vulnerabilities of his time. His legacy is not just one of brutal murders but also of the profound social anxieties of Victorian London, the limitations of early forensic science, and the enduring human fascination with unsolved mysteries. The tale of Jack the Ripper serves as a chilling reminder of the darkness that can lurk within society, forever captivating our imaginations and prompting us to ask: who was Jack the Ripper?